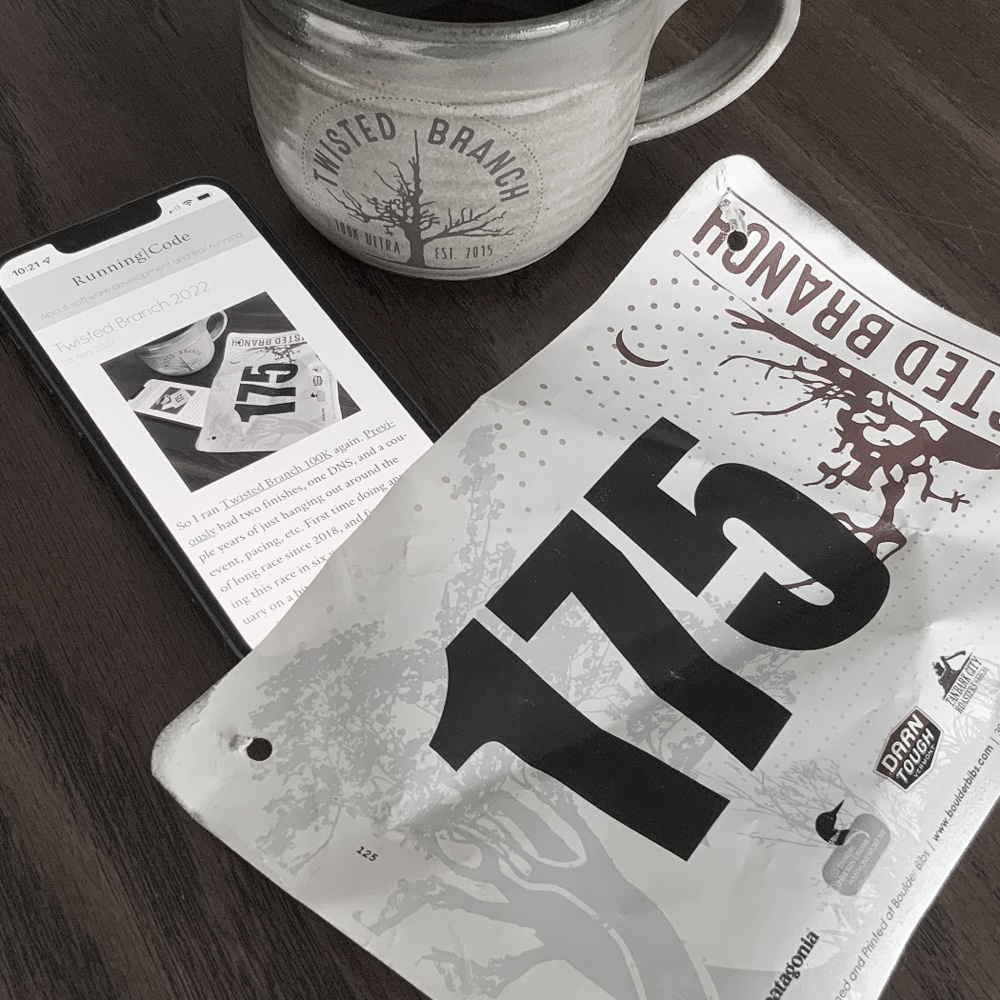

Twisted Branch 2022

So I ran Twisted Branch 100K again. Previously had two finishes, one DNS, and a couple years of just hanging out around the event, pacing, etc. First time doing any sort of long race since 2018, and first time starting this race in six years. Signed up in January on a bit of a whim, wasn’t sure if I could survive the race anymore, let alone match what was very plausibly a long-past period of peak performance.

But in the end, this race set the framework for an entire season of some of my best training and possibly the best fitness level ever. I finished the race with a new PR, and more importantly emerged with a much improved perspective on running and racing.

♥️🍪♥️

First: thank you Valerie, crew extraordinaire, listener, coach. Unfailingly accepting of every silly adventure. Always knows exactly what I need to hear. Impossible to imagine this life without you as a partner.

Inspiration

Strat and Jeff and Laura: my adventure partners over all these years. Back in my peak racing years of 2015–2016, was just getting to know them, and they were inspiration to do more and a catalyst for many other new experiences and friendships. Between then and now, an endless wellspring of hard, weird, easy, long, simple, creative, questionable adventures. Always ready to jump in on some oddball idea, always easygoing, no pressure, just acceptance. Memories that I now can draw on for any situation, knowing that a person can achieve anything (or can just take a break and relax).

Abby M: just drops these mythical adventures and enormous feats out of nowhere. Couldn’t stop thinking about Abby’s performance at Vol State 500K, and Laz’s chronicles of the race. Abby has this way of casually stepping into the unknown, marching through unimaginable hardships, and emerging often victorious but always transcendent and wiser. And then sharing the experience in an authentic, relatable, instructive way. But also clearly training hard, thoughtfully preparing for the day, and getting the most out of gear.

Jamie H: keeps showing up year after year, constantly improving, training with method and precision, knowing exactly when to apply big volume, when to recover, how to cross-train.

The new Rochester trail community: it’s a new generation since I was in the game. Don’t know many of the new people, but it’s clear from those I have met (e.g. Cruz and Clement) that it’s more positive and inclusive than ever. The future has hope.

And in the moment of this race: I was trading places all day with a handful of runners; they were stronger on the hills and flats and I caught up on the descents. Their consistent work mile after mile gradually pulled me further out of the comfort zone over the day, rekindled the muscle memory of the Tactics of Racing, and finally helped me push beyond the boundary of what I thought would be possible.

Method

After 2015 (the first year of Twisted Branch, and overall what I feared was my peak of running and racing, forever out of reach), my racing performance lacked any consistency. A few decent results but a lot of DNS, DNF, or just lazy efforts. Much of this was clearly attitude: hubris, a lack of discipline, caring too much about the result or expectations without putting in the work to make it happen. Too relaxed in the wrong ways, not relaxed enough in the wrong ways.

After taking a few years off of racing and just doing some low-key adventuring, I finally felt ready to try it again. Valerie accurately predicted that having a big goal race an entire year away would give some proper structure and motivation to training. It worked.

In those years of failure, my training focused too much on hard numeric goals and endless escalation of volume. Small hiccups—missing a mileage goal, unexpected schedule disruptions, a single bad run—would easily send me spiraling and I would lose weeks of work at critical times. This year, with the benefit of self-awareness and a long time away from all that, I tried to avoid these mistakes.

I don’t use a coach or have a grand plan for training. When ready I start a training cycle that lasts several weeks, execute it one week at a time, and then when it’s time to rest the cycle ends, and starts again after a couple of easy weeks. Each training cycle had some rough overall goals, not numeric, just concepts to improve on. Each Monday I assess the schedule and weather, assemble a rough plan, come up with a couple of specific key workouts, and choose some cumulative numbers to target for the week: distance, time, training impulse, or elevation gain. Time and training impulse are useful metrics for cross-training to feel more worthwhile and not like wasted time.

Many weeks don’t go as planned: a key workout is missed, a number isn’t quite reached, the schedule goes off the rails. Maybe I go way beyond the goal, or pivot to some different goals mid-week. When the week’s over I accept it as just one stone in the bucket of the training cycle and account for that result when planning the next week. No individual workout or week is a failure that will break an entire season. A great performance isn’t permission to stop and say that’s good enough, just move on to the next week and keep building.

And—I’ve always believed this but now I consider it a central tenet essential to healthy training—every individual workout needs to have some sort of purpose. That purpose might be discovered or changed mid-workout, and it might be simple or banal (e.g. “just enjoying the sun”), but it has to be there. Rest or simply goofing off is better than junk miles.

A lot of this happens to align with Jack Daniels’ training methods (recommend Jeff Green’s thoughts), for what it’s worth. Mostly coincidentally, though I’ve been vaguely familiar with it.

The late winter/early spring training cycles were mostly focused on base building and gradually elevating aerobic capability, with lots of road mileage and interval workouts. I leaned heavily on heart rate training and steadily increased pace to stay in the HR zones as fitness increased; eventually this unlocked a faster “easy” pace than I had thought was appropriate in past years. Measured progress via VO2 max and 10K/half marathon time trials (and PRs). One capstone effort was a five-day streak of 3+ hours running/cycling each day (across the full range of Rochester’s March weather), totaling 77 mi running, 37 mi biking, 15h total time.

Spring and summer cycles added trail and hill work, lots of heat/humidity acclimatization, and occasional (but not too many) long runs or hikes. Plenty of trips to the mountains. Long mountain hikes and runs are my favorite recreational application of running so this broke up the monotony of just doing long runs every weekend. A big hike is a nice way to build experience with very long days, and have a massively shorter recovery time (and less risk of injury/overtraining) compared to extra-long training runs. I have lots of long-term goals in the Adirondacks, and constructing adventures to chase these goals was a nice way to build and test ultrarunning skills. This culminated in my two longest-ever ADK hikes, some cool adventures, finishing the 46 high peaks, and my biggest ever week in total climb (21,838 ft) and time (29h).

As the race drew closer, I actually paid attention to hydration and calorie tactics: previous years of racing I either overdid it, or later thought I didn’t need much of anything. Lots of reading, experimenting, and testing led me to confirm I actually do prefer low intake. So I built a structure for the race which allowed for that but ensured there was a consistent baseline to stay out of the weeds: a single chewable and a sip of water every 15 minutes which amounts to 5–10 oz water and 60 calories per hour. Once per hour or so, larger intakes of food and water would add more bulk as needed, settling around 100 cal/hr for mountain hikes and 200 cal/hr for running, and water around 5–15 oz/hr depending on weather and effort. [This is not prescriptive, the difference in ideal intake from person to person can be massive. Just find what works for you, and actually test it before a race.]

The final training cycle ended in “dress rehearsals” for Twisted Branch: back-to-back 50K runs on the race course, in the exact clothing/gear configuration for race day, aiming for the target race pace, following the race plan for water and calories. They went pretty smoothly, met the pace goal, validated the water/food plan, and sorted out a few mistakes and gear issues that could have really messed up the race. They gave me some assurance on race day that I had a solid plan for a PR.

Overall, the idea was to eliminate as much guesswork and unnecessary decisions during the race as possible. Control all the variables that I could and avoid unforced errors, so I could focus my mental and physical energy on responding to the inevitable vagaries of the day that are not controllable.

Trust

This year, and this race, after years of absence and fearing failure, was an exercise in trust. Learning to trust friends, that they really are up for spending long days doing silly things, and that it’s ok to ask for help. Even simple things like asking for a ride (thanks Laura!).

In past years, I got through this race with luck and the brute force of youth. This year, I made a bet on experience and scientific method to maximize what’s left of any talent I had and avoid as many mistakes as possible. Methodically building fitness and refining strategy, and during the race trusting that that work would carry me through to the end.

In the early miles of an ultra, it’s easy to look at what’s ahead and despair that you won’t be able to maintain goal pace for the whole day. Those dress rehearsal runs gave me some solid evidence to trust that the plan was going to work, to quiet the nerves and just keep moving.

Letting Go

My past racing career ended with increasingly unrealistic internal expectations and fear of (perceived) external expectations. Comparing to others. Ultrasignup scores. Fear of letting others down. Getting hung up on missing smaller goals, which led to being unprepared for larger goals. Bad mindsets all around.

This year was an exercise in letting go of all of that. After years of avoiding racing, and just adventuring with friends, finally felt ready for a fresh start. I had this dual, maybe dissonant mantra of “no expectations, nothing to lose”.

I’d like to think that being self-reliant in the wilderness has cultivated a mindset that is much less dogged by the fear of failure. Not “failure is not an option”, more like “failure doesn’t exist as a concept in my brain”. On a long day in the wilderness, that literally is how you have to operate: the only thing you can and must do is get to the next summit, and then get home. There is no option to quit. I mean most days are not extreme, it’s not Antarctica, you can cut the route short, etc., but there is always some level of responsibility to take care of 100% of your own basic needs until it’s finished. The only way out is through.

Mountain running and off-trail navigation, even more than trail running, puts one into moments of total focus and flow. The puzzle and art of moving quickly over mountains and through unbroken forest is to answer with every step “how best do we get to the next point” and “how do we perform the next move in this scramble”, not “can we even get up that entire thing” or “do we feel like doing some more miles”.

So in the race, I tried to stay in that flow. Going mile to mile, aid station to aid station, focusing on what was required for that moment, letting go of what happened in the hours before or what may or may not unfold in the hours ahead. Breaking down that scary “can I finish this race” question into the simple tasks of “what’s the best line down this hill”, “can we jog a little more on this easy part”, “sweat rate is dropping, have an extra sip”.

I see Twisted Branch as a play in three acts. Miles 0–21 are the warmup: keep it easy. 21–46 are the critical ultrarunning miles: avoid mistakes, keep grinding, don’t lose your way (figuratively or literally) in the mental purgatory between The Lab and Bud Valley, and have the strength and skill to handle the escalating effects of whatever (hot or wet) weather the day has to offer. And then 46 to the end is where you race.

I leaned on all that planning to get to mile 46. Was still basically right on time to match and hopefully beat my best time. Body was still feeling strong. The main thing left to face was that fear of failure, the aversion to actually finishing a thing and doing it well, going beyond the easy and comfortable.

I was fortunate to be keeping up with a few cool people all day, and now chasing them down would be the catalyst to push a little harder. The climbs and miles ticked by, and each one was a mini-race, an attempt to keep up with the goal pace, to try to figure out how to break that mental barrier of trying harder. Finally, the pieces fell into place: I relaxed, remembered to stay in the moment, solve the problem at hand, stop caring about the numbers, and just go. I finally let go of everything and just ran. No expectations, nothing to lose.

The End

The final miles were a fun experience. Almost lingered too long at the last aid station; the hot coca cola and Valerie’s tough (and perfect) coaching were the slap in the face to just get moving and finish before the PR fell out of reach. Mount Washington was what it always is. Just climb. Then some unknown (I always forget) number of miles over a weird rolling ridge with your mind no longer functioning, and a long descent dumping straight into the finish line.

For “reasons”, my watch only had time and heart rate metrics visible, and I was so close to the PR threshold I really had no idea if I could get it. I think this worked well actually to let go one final time, just run all out, no expectations, nothing to lose. Somewhere on the ridge I fell, knowing the legs were threatening to cramp, but somehow I willed them to keep moving. A little steep rough descent down a drainage, finally sort of knew where I was as it levels back out, smoother and more runnable than I remembered, turned up the pace again.

You get a tease of the final downhill on some pavement (6:57 pace), then a stupid mean climb that everyone hates (ran almost the whole climb this year), then the final descent, increasingly steeper and rougher. Tumbling down the hill, bouncing off each switchback, tunnel vision, every step an eternity of focus to stay upright and find a survivable line through the loose shale and roots, only at the very end with the crowd audible and the finish visible through the trees did I finally know a PR was actually happening. Across the road, stumbling through the finish, crumpling onto Valerie. Immobile on a cot, finally my legs had permission to give up and cramp. And finally a properly cold drink. The sun was still up. Lots of cool people everywhere. A nice evening.

Anyway,

Good times. Party. Data on Strava.

Do you like gear? Here’s what I used for the race:

- Shoes: VJ MAXx. Somewhat overkill for this race (VJ Ultra would be more sensible for most people), but the Ultras were doing a weird thing with my ankle and the MAXx had proven themselves to be absolutely reliable through everything after many long days in the mountains. And surprisingly comfortable, even at the end of a 13 hour hike. It’s nice to literally not have to think about your shoes or feet at all, to unconditionally trust that they will carry you over anything, while stumbling down a rudely steep descent over roots, grass, and loose shale at mile 55.

- Smartwool crew socks (long sock club)

- Shorts: Rabbit Shredders. These things stay dry and lightweight through the wettest and nastiest sweatiest days, and have an incredible pocket system. Like I was carrying 800 calories, electrolyte tablets, and a buff, all instantly accessible, comfortably, with no bounce.

- Shirt: Rabbit tank. Light and cool. A big fan these days of tri-blend shirts—shop at Beckhorn Prints for the best designs—but I learned on that 50K dress rehearsal that the hottest long runs are maybe a little too much for them.

- Trucker hat from Beckhorn Prints. Well, three. No change of shoes or shirt during the race but a fresh dry hat & Buff every 20 miles was a simple luxury.

- Petzl headlamp

- 2Toms is essential. Try it between your toes, too.

- Black Diamond Distance 8 pack. Packs and vests are hard to figure out, everyone has different needs; the Distance packs are my favorite because they ride supremely comfortably, have a great front pocket system, and are super durable and versatile.

- In the pockets: calories and electrolytes, and a Buff, in shorts pockets (see above). Trash secured in the back shorts zipper pocket. One soft flask in the front vest pocket with one of those long straws. An S-Biner secured the straw to a loop on the pack at just the right position. Phone in a front pocket. Back compartment of the vest: a quart bag with backup gear (socks, spare shoelace [helplessly witnessed a shoelace break while pacing once, and vowed to never be without a spare shoelace ever since], tiny med kit, toilet supplies), and an extra water flask (only used it on one long segment between aid stations).

- The gear list for crew was hilariously long; what actually got used included some extra calories (Skratch gummies and Spring speednuts), electrolyte tablets and fluid concentrate, a dry towel, a wet towel, those spare hats & Buffs, and headlamp handoff/return. Trekking poles were queued up for the last segment but I declined.

Thanks.